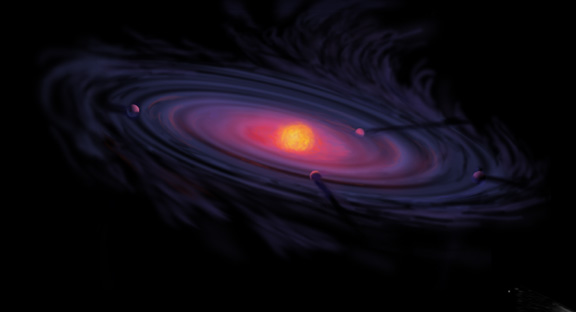

It is not known with certainty how planets are formed. The prevailing theory is that they are formed during the collapse of a nebula into a thin disk of gas and dust. A protostar forms at the core, surrounded by a rotating protoplanetary disk. Through accretion (a process of sticky collision) dust particles in the disk steadily accumulate mass to form ever-larger bodies. Local concentrations of mass known as planetesimals form, and these accelerate the accretion process by drawing in additional material by their gravitational attraction. These concentrations become ever denser until they collapse inward under gravity to form protoplanets. After a planet reaches a diameter larger than the Earth's moon, it begins to accumulate an extended atmosphere, greatly increasing the capture rate of the planetesimals by means of atmospheric drag.

An artist's impression of protoplanetary disk:

When the protostar has grown such that it ignites to form a star, the surviving disk is removed from the inside outward by photoevaporation, the solar wind, Poynting-Robertson drag and other effects. Thereafter there still may be many protoplanets orbiting the star or each other, but over time many will collide, either to form a single larger planet or release material for other larger protoplanets or planets to absorb. Those objects that have become massive enough will capture most matter in their orbital neighbourhoods to become planets. Meanwhile, protoplanets that have avoided collisions may become natural satellites of planets through a process of gravitational capture, or remain in belts of other objects to become either dwarf planets or small bodies.

The energetic impacts of the smaller planetesimals (as well as radioactive decay) will heat up the growing planet, causing it to at least partially melt. The interior of the planet begins to differentiate by mass, developing a denser core. Smaller terrestrial planets lose most of their atmospheres because of this accretion, but the lost gases can be replaced by outgassing from the mantle and from the subsequent impact of comets. (Smaller planets will lose any atmosphere they gain through various escape mechanisms.)

With the discovery and observation of planetary systems around stars other than our own, it is becoming possible to elaborate, revise or even replace this account. The level of metallicity – an astronomical term describing the abundance of chemical elements with an atomic number greater than 2 (helium) – is now believed to determine the likelihood that a star will have planets. Hence, it is thought that a metal-rich population I star will likely possess a more substantial planetary system than a metal-poor, population II star.

The Nebular HypothesisThe Nebular hypothesis is the most widely accepted model explaining the formation and evolution of the Solar System. There is evidence that it was first proposed in 1734 by Emanuel Swedenborg. Originally applied only to our own Solar System, this method of planetary system formation is now thought to be at work throughout the universe. The widely accepted modern variant of the nebular hypothesis is Solar Nebular Disk Model (SNDM) or simply Solar Nebular Model.

According to SNDM stars form in massive and dense clouds of molecular hydrogen—giant molecular clouds (GMC). They are gravitationally unstable, and matter coalesces to smaller denser clumps within, which then proceed to collapse and form stars. Star formation is a complex process, which always produces a gaseous protoplanetary disk around the young star. This may give birth to planets in certain circumstances, which are not well known. Thus the formation of planetary systems is thought to be a natural result of star formation. A sun-like star usually takes around 100 million years to form.

The protoplanetary disk is an accretion disk which continues to feed the central star. Initially very hot, the disk later cools in what is known as the T tauri star stage; here, formation of small dust grains made of rocks and ices is possible. The grains may eventually coagulate into kilometer sized planetesimals. If the disk is massive enough the runaway accretions begin, resulting in the rapid—100,000 to 300,000 years—formation of Moon- to Mars-sized planetary embryos. Near the star, the planetary embryos go through a stage of violent mergers, producing a few terrestrial planets. The last stage takes around 100 million to a billion years.

The formation of giant planets is a more complicated process. It is thought to occur beyond the so called snow line, where planetary embryos are mainly made of various ices. As a result they are several times more massive than in the inner part of the protoplanetary disk. What follows after the embryo formation is not completely clear. However, some embryos appear to continue to grow and eventually reach 5–10 Earth masses—the threshold value, which is necessary to begin accretion of the hydrogen–helium gas from the disk. The accumulation of gas by the core is initially a slow process, which continues for several million years, but after the forming protoplanet reaches about 30 Earth masses it accelerates and proceeds in a runaway manner. The Jupiter and Saturn–like planets are thought to accumulate the bulk of their mass during only 10,000 years. The accretion stops when the gas is exhausted. The formed planets can migrate over long distances during or after their formation. The ice giants like Uranus and Neptune are thought to be failed cores, which formed too late when the disk had almost disappeared.

Topic: WHO MADE THE WORLD

Topic: WHO MADE THE WORLD